Jordan Hyche | August 30th, 2025

Born on Independence Day 1924, Arthur Cundy Jr., was one of two sons in a proud American family. Interestingly enough, his mother, Virigina was a direct descendant of Francis Scott Key; the author of our national anthem and Arthur Sr. served as a Captain for both the British and United States during the Great War. As Arthur Jr. and his younger brother David grew into teenagers a family decision was made to carry on their patriotic upbringing and family legacy. The two would soon leave Shades-Cahaba High School in Birmingham and enroll into the Georgia Military Academy outside of Atlanta. Arthur Sr. and Virginia followed suit into duty for their country; Virigina volunteered for the Womens Auxiliary Corps (WAC) shortly after the United States entered World War II and Arthur Sr. applied for a recommission in the U.S. Army. From then on the family would be known as the “Fightin’ Cundy’s” among their friends and neighbors.

In 1942, the two Cundy brothers had excelled in their military classes, leaving an impacting impression on the faculty at the academy. So much so, that during Arthur’s May 1942 graduation he was presented with the Georgia Military Academy’s coveted Townes Medal. The medal exhibited the highest moral excellence among the 450 students, a proud honor for any cadet to accept. It just so happened the following year, David would be awarded the medal as well. A brother duo winning the award was a first in the rich history of the Georgia Military Academy. After leaving the Georgia, Arthur Jr. attended the University of Alabama for a short period prior to beginning his December enlistment in the U.S. Army Air Corps.

While Arthur’s stay in Tuscaloosa was short lived, the personal relationships and social impact he built lasted beyond measure. As a cadet in Georgia, he developed an enjoyment for reading and writing and was drawn to the same crowd while at the University of Alabama. That’s where he befriended the editing staff of the beloved monthly magazine, The Rammer Jammer. Arthur would never forget his friends located on the third floor of New Hall and vowed to write them weekly once in combat. He would also find a way to carry on the catch phrase, Rammer Jammer but how was still up for debate.

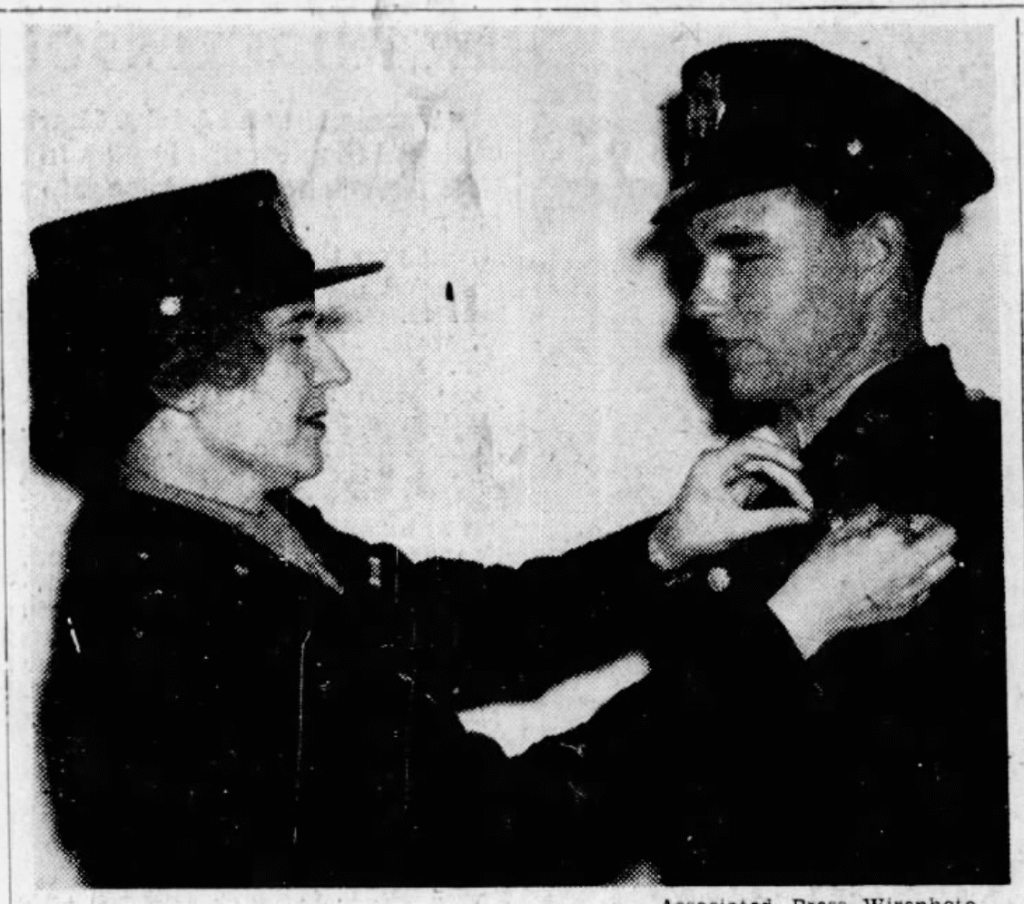

Second Lieutenant Cundy’s 1943 was full of aerial combat training and learning his new craft. From Florida to Kansas and Texas, he continued to hone in his confidence behind the cockpit of the North American AT “Texas” and the P-40 “Warhawk”. He developed a true love as a pilot towards the free feeling of flying. As November arrived, so did a surprising and loving visitor, his mother Virginia. She surprised him at his Pilot’s Commission Ceremony at Aloe Army Airfield and proudly pinned the silver medallion pilot’s wings upon her son’s chest. His training and love for family and country led to this moment and now was his opportunity to join the brotherhood in the sky to push back against German aggression across Western Europe.

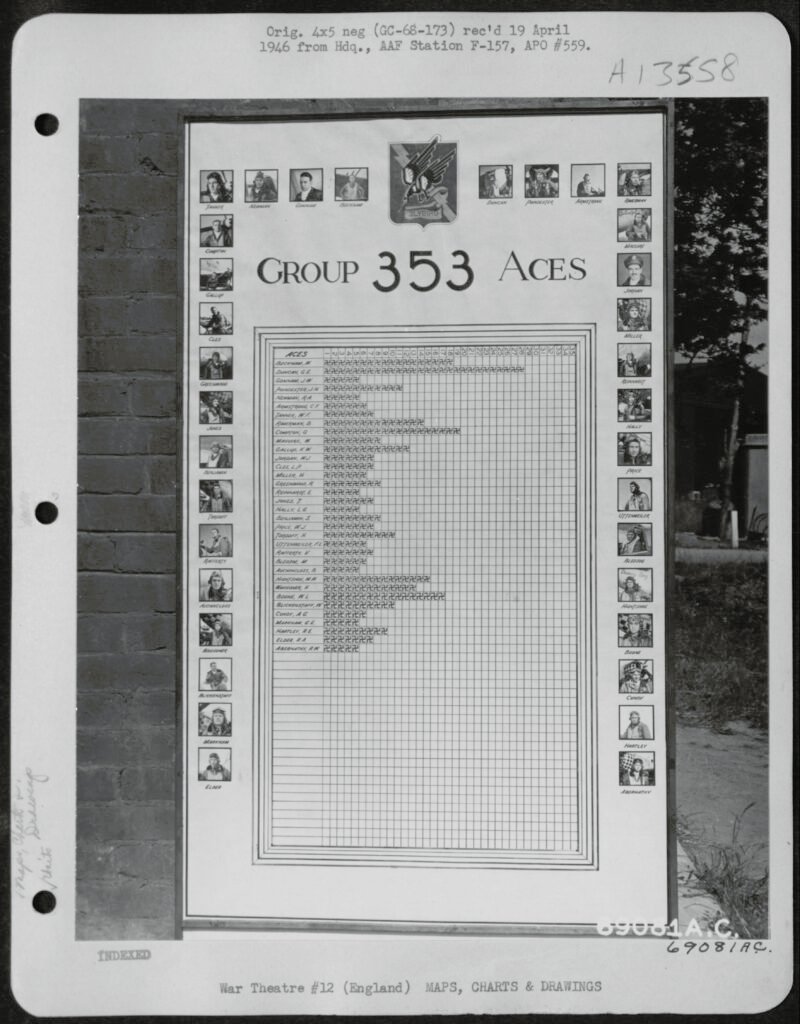

Approximately six miles west of the city Ipswitch on England’s eastern coast and nearly sixty miles northeast of London lay Raydon Airfield, known as USAAF Station 157 to the boys of the 352nd Fighter Squadron. Along with the 350th and 351st Squadrons, they together made up the 353rd Fighter Group which first began action against Nazi Germany in June 1943. This fighter group was attached to the mighty 8th Air Force, led by B-17 Flying Fortresses, which gained national fame with some of the most proficient bombing raids in the war thus far. However, those heavy bombers required protection in the clouds becoming prone to significantly high and unsustainable loss rates typical during any given mission. Loss rates that attributed from both flak shelling and German Luftwaffe patrols. That’s where the pilots of the 353rd Fighter Group came to aid the ‘Bomber Boys’ and together in unison punch through Axis skies.

In August 1944, a newly trained fighter pilot arrived in their ranks. A clean cut, confident twenty-year-old Alabama boy by the name of Arthur Cundy Jr. The 352nd, of which Cundy was assigned to, was still flying the bulky P-47 Thunderbolts. Their maneuverability and speed lacked where their German counterparts, the Messerschmitt 109 and Focke-Wulf 190 excelled but that was soon to change. In October, the fighter group obtained the newly designed P-51D Mustang which boasted better visibility, superior flight range and could move step for step with both German aircraft. By mid-November the entirety of the 352nd Squadron had the P-51D and became well trained on their new steed in aerial combat. It was also the month when 2nd Lt. Cundy Jr. was presented with the meritorious Air Medal with Oak Leaf Clusters, an attribution of completing ten missions, and collected his first downed enemy, an Me 109 on November 27th. His faith in the P-51 grew and a few short weeks later during a Christas Eve mission he added another enemy to his scratch card, an Fw 190. Not only was Cundy blossoming as a pilot, but he was seen as a leader among his buddies in the squadron and his commanding officers. In January 1945 Arthur was promoted to 1st Leuitenant and moved from being a wingman to an element leader.

With this newfound fame among his fellow pilots and aircrew, Cundy never forgot his Alabama roots nor his friends back in Tuscaloosa. He wrote them weekly giving the group firsthand stories of what life was like in England and his aerial combat stunts. The magazine affected him so much so that he decided to unveil the name of his P-51, “Alabama Rammer Jammer” in honor of his friends at the university. The deep crimson lettering across his Mustang’s nose beamed in the sunlight, and his ship of the sky became Arthur’s true love. It wasn’t long into 1945 when he would receive his third kill, another Focke-Wulf 190, Lt. Cundy was now two downed enemy aircraft away from becoming an Ace in the 352nd Squadron. A rare feat to accomplish and every combat pilot’s dream.

The morning of March 2nd began like any other at Raydon Airfield. Another early predawn mission briefing, stout black coffee, uncalming nerves and P-51 Packard Merlin engines firing in staggered unison. The day’s mission was in support of 8th Air Force’s B-17’s on their bomb run across oil refineries north of Dresden, Germany in the Eastern Ruhr. All was quiet in the sky until the bombers reached their target. ‘It was a long time since I’d seen so many Jerry fighters up against bombers’, recalled Cundy during his mission debrief hours later. The sky became cluttered with aircraft, both friendly and enemy. Suddenly an Me 109 above Alabama Rammer Jammer dove straight into the Mustang’s formation, Cundy described the fighter as ‘Superman and Hitler rolled into one’. Lt. Cundy saw his chance and jumped on the tail of the 109, chasing it as the plane skied upward towards the B-17 Flying Fortresses. The two pilots suddenly stalled and fell towards the deck as they squeezed shots at one another. The brief chase was on but ended abruptly once the Me 109 pilot noticed Cundy was still behind him firing. In choosing to live another day, the German jettisoned his plane and hit the silk, parachuting towards the ground beneath. Lt. Cundy marked up his first downed enemy of the day as he zipped alone underneath the cloudbank. By this point the entire squadron was scattered and “Ram”, as Cundy often called his plane, set out to find his wingman but instead found another German Me 109. ‘I got up right behind him and blew him up without making a move to evade’, the Alabamian explained. Evidently the lone pilot never noticed Alabama Rammer Jammer as it approached his six. After scoring his second target of the day and with fuel tapering by the minute, Cundy turned for home. Breathing a sigh of relief and a bit of a pat on his own back, Arthur Cundy Jr. was now an accomplished Ace after recording his 5th downed German plane since arriving in the British Isles back in August 1944.

His lone, self-gratification didn’t last however, in his sun glared mirror Cundy noticed a small spec across the horizon. Feeling curious and unsure if the dot was friendly or foe, he broke left after it. The dot turned out to be an unfriendly Fw 190, ‘we came at each other head on, both firing’, as his hands gestured the scene to his buddies afterwards. Cundy’s hits were true and the Fw 190 exploded leaving sharp hot metal drifting downward. His third kill of the day ended in a triple victory and marked his overall total to six downed enemy aircraft. Arthur would become revered in local newspapers back home from his mother’s birth state of Kentucky to his home state of Alabama, and onward to friends in New Hall at the University of Alabama.

One would think a combat pilot’s greatest accomplishment would be becoming an Ace in his squadron, but Lt. Cundy was humble enough to realize his role as a flyer was much bigger than that. He attributed his greatest thrill not towards daring adrenaline heightened dogfights but to ensuring the bomber boys and his friends made it back from missions safely. In early December 1944, Arthur explained the feeling of gratitude he felt when assisting his wingman and three B-17’s back home from a mission over Merseberg, Germany. After helping his wingman, Lt. Donald Schoen reach the English coastline after experiencing engine trouble, Cundy turned and noticed another aircraft hopelessly limping back home. It was a B-17 by the name of “Lucky Strike” piloted by Lt. Arthur S. Taylor Jr. of the 490th Bomb Group. After losing their engine, the crew decided it was best to turn around and head for their air station in Suffolk, England. Lt. Cundy spotted the crippled fortress after assisting Donald Shoen home. ‘I thought we were through for the day but then we spotted Lucky Strike’. Cundy watched as the drifting plane weaved alone, flying dangerously low. The Lucky Strike had been fortunate to reach the English Channel. Arthur then described the damage in detail, ‘the right outboard engine was shot out, the fuselage was pock-marked with flak holes and the right wing was torn up like a shell had passed through.’ He and another P-51 circled the struggling B-17 until it reached the safety of home. It wasn’t until later when Lt. Cundy and Lt. Schoen found out the Fortress was merely flying on the acts of its flight engineer’s impromptu rigging of control cables in his heated jacket. To the boys of Lucky Strike, the Alabama Rammer Jammer ‘looked like an angel from heaven’, as described by one crewman. By sunset that evening he would help two more fortresses reach the sight of friendly skies. A few days later, Cundy and Shoen made the short drive up to Eye Airfield in Suffolk for a special visit. It was the home of the Lucky Strike crew, and their handshakes were heartwarming. ‘Those bomber boys really have a tough job’, Cundy declared as the boys reminisced. He continued. ‘it’s a privilege to help them out when the going gets rough.’ As their time together closed, Arthur turned to his buddy and smiled, ‘meeting those fellas is more pay than I’ll ever want for any job I’ll ever do’.

Regrettably, 1st Lt. Arthur Cundy Jr.’s love for the sky and flight would be star-crossed just over a week after becoming an Ace. On the morning of March 11th, 1945, he piloted “Miss Jackie II”, the P-51 of his friend Lt. Lindsay Grove, on another heightened mission over Germany. Over the North Sea and enroute to the target, Miss Jackie II developed a coolant leak. An engine failure that typically turned deadly for any P-51 pilot who experienced it. Lt. Cundy radioed to his wingman that he was turning back towards Raydon but unfortunately watching his plane dip beneath the clouds would be the last anyone would ever see of Arthur Cundy Jr. It was later surmised that Miss Jackie II exploded over the North Sea, leaving the twenty-year-old Cundy, Missing in Action presumed Killed in Action. In the end he had given his full devotion to our country from childhood to his final moments enjoying the sky over Europe. He was up for promotion after becoming an Ace, but that would be received posthumously. Captain Arthur Cundy Jr. would be his final designation and along with it he’d be honored with the Distinguished Flying Cross, Purple Heart, and finally upon his Air Medal of which he received three months earlier, 9 prestigious Oak Leaf Clusters. On England’s rolling countryside outside of the historic city Cambridge lies in honor, over 3,800 American War Dead and inscribed upon the Cambridge American Cemetery’s Wall of the Missing are 5,127 names of American boys never to return home. One of which being the Alabama Rammer Jammer’s pilot, Capt. Arthur C. Cundy Jr.

Sources: 353rdFighterGroup.wordpress.com | Tom Cleaver | National Archives

Excellent story. I look forward to reading your work. Thank you for all you do.

Jordan, I appreciate your dedication to sharing historical accounts and, more importantly, the stories of ordinary soldiers from the Greatest Generation. Your efforts are preserving valuable histories that would otherwise be forgotten. Well done, and best regards.

Well done Jordan, well done.